“Stranger Things”, the new much-hyped Netflix show created by Matt and Ross Duffer, is an enjoyable romp. It’s a love letter to the past in a way that has become very fashionable these days. It borrows more sentiments from its Eighties influences than Melania Trump borrows from Michelle Obama. Of course, as every artist would rightly argue, all this borrowing does not constitute stealing. It’s not a rip-off. It’s a “homage”.

But where exactly do you draw the line? When does a self-aware nod become a straight up rip-off? At what point does “homage” become stealing? Can an homage ever be theft? It’s tricky because in art everybody steals from everybody. As Lawrence Olivier once said, “Good actors borrow, great actors steal”; and even then he probably stole that line from somebody else. What I find more interesting is what writers and directors actually do with the material that they’re referencing. Quentin Tarantino, to take a well-known example, does something special: he makes it his own. He manages to take the unmistakable cinematic language of a filmmaker like Sergio Leone and put his own spin on it, creating a cinematic form entirely of his own. Jimi Hendrix took what Muddy Waters was doing in the 50s and created his own unique style of guitar playing that revolutionised the instrument and, in turn, modern music. But some artists just take what others have already done before them and bring nothing original to it at all – nothing of themselves.

For me, “Stranger Things” often falls into this category. There has been much written about the influences of “Stranger Things”: from the creepy science-fiction tales of Stephen King to the suburban adventures of Steven Spielberg. There is absolutely nothing wrong with having any of those influences (obviously). However, there is a difference between producing your own unique vision of an inspiring work and merely reproducing that inspiring work. You must remember to bring your own thing to the table. And while people like King and Spielberg bring something to table, “Stranger Things” arrives to mooch off everybody else.

Just take a look at how explicit the referencing of “Stranger Things” is with regards to its influences. And not only that, but also how little effort there is to try and make any of these touchstones overtly “its own” or offering a unique take on the material.

Here’s short a (somewhat facetious) quiz.

- A bunch of kids encounter and befriend a strange creature that can perform incredible things with its mind. The Government meanwhile want to seize control of it, forcing the kids to dress the creature up as a girl to avoid detection.

So, is this “E.T.” or “Stranger Things”?

- Nancy, a teenager girl, attempts to lure a monster from another world into a home where she strategically laid booby traps for its capture.

What do you think? “A Nightmare on Elm Street” or “Stranger Things”?

- A mother tries to rescue her child from another dimension inside her family home as she struggles to communicate with the static noises and echoed voices of her kid.

Well? “Poltergeist” or “Stranger Things”?

And here are two purely visual examples for comparison.

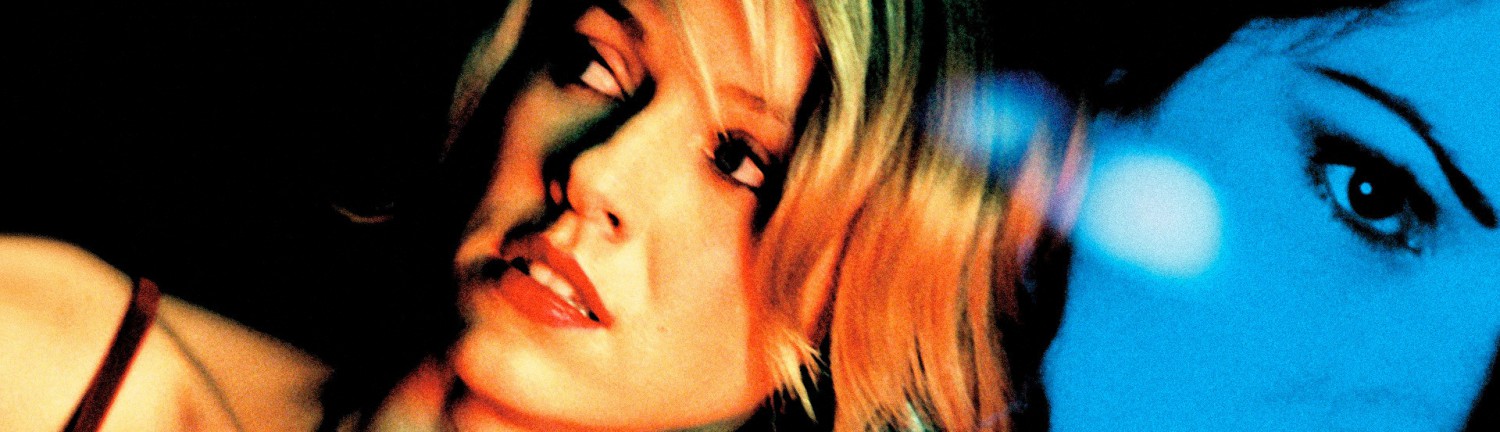

- “Under the Skin” or “Stranger Things?”

- “Alien” or “Stranger Things”?

There are numerous references, nods and allusions like these throughout “Stranger Things”. But I can’t help but feel that they primarily exist to (a) act as a cheap way of giving the audience an extra grounding in that period, or (b) to steal the visual audacity of an under-seen work (which seems to the case with the “Under the Skin” motif – after all, there’s no real thematic or contemporaneous connection between the two works that would make referencing it particularly appropriate). It’s almost as if the creators think the aesthetic of the Eighties can only be achieved by referencing Hollywood movies of that era. And after a while, it just becomes referencing for the sake of referencing.

But there’s a catch. If you “get” the reference (‘Oh I see, this part with the kids on the railroad is a nod to “Stand by Me”’) then you may clever for having spotted it. But if you don’t get it, like if you’ve never seen “Stand by Me” or read Stephen King’s “The Body” (which is totally fair game, by the way), then you may think that what you’re seeing is entirely original. If you’ve never seen any of the movies “Stranger Things” is referencing (constantly, mind you), then you’re bound to think “Stranger Things” is more original than it actually is.

The nostalgic referencing in “Stranger Things” isn’t an anomaly. It’s part of a much wider modern tradition of constantly referencing movies from one’s childhood – often without wit or originality. The latest “Jurassic Park” film, “Jurassic World”, references Spielberg’s original in almost every frame. It constantly panders to its fans but has nothing new to offer other than sheer scale. “The Force Awakens” does a similar sort of thing, keeping audiences happy with constant nods and in-jokes to the original trilogy instead of telling its own story (however, this is done with much more skill here than in “Jurassic World”). The new “Ghostbusters” movie never stops referencing the original film either. Many gags solely serve to remind audiences that they’re watching a remake, and the film greatly suffers as a result. The first half-hour of the latest “Terminator” movie, “Genisys”, was essentially a remake of the first two movies, supplying more nods to its audience than Angus Young at a rock concert.

Spielberg, one of the filmmakers the Duffer brothers hold in high regard, often took elements of films he loved as a child and inserted them into his films as a director. But unlike the modern trend in television and cinema, he didn’t simply take whole chunks of the films – their plots, their storylines, their indelible visuals – and insert them into his own; at least not without appropriating them in such a way that they became his. No. He was inspired by them, yes, but he also learned from them – their technique, their craft, their approach – and then he learned how to make it his own. Instead, many modern TV shows (and especially films) are acting like tribute bands to far better musicians.

There is a right way to do this referencing business. See the TV-version of “Fargo” for proof. “Fargo” makes many references to the work of the Coen brothers. But each time it does so it almost always serves a thematic purpose, not just to say to audiences “Hey look, this scene is just like that bit in ‘Miller’s Crossing.’”

All of this isn’t to say that “Stranger Things” isn’t worth watching. It is. All the hype it’s generated isn’t for nothing. Like I said before, it’s an enjoyable romp. It’s fun, it’s entertaining, and there are some terrific performances throughout – particularly from the kids (the incorrigible, smiley Dustin, played by Gaten Matarazzo, being a standout). It’s also got some of the best sound design of any film or TV show I’ve seen this year, for which I applaud sound editor Brad North and sound designer Craig Henighan. The show is also impressively shot by DPs Tim Ives and Todd Campbell. The night scenes in particular have a visual aesthetic that gorgeously heighten the eerie scenarios faced by the characters. It’s just that “Stranger Things”, in terms of narrative and inventiveness (and even strangeness) is nowhere near as interesting nor as original as most of the stuff it’s referencing. “Stranger Things” is a well-made pastiche of Eighties classics. But, much like its central character Eleven, it has very little to say for itself.