This week sees the 125th birthday of director Ernst Lubitsch. If you don’t know who that is, here’s why I think you should:

“Germans aren’t funny.” You hear this cheap crack all the time. A bunch of ruthlessly efficient, incredibly rational hardworking pragmatists – but ask them to tell you a knock-knock joke and you might as well be watching an Adam Sandler movie. In 2011, a poll was conducted in which more than 30,000 people from 15 different countries were asked to rank the nations with the worst sense of humour. Germany came out on top (or bottom, depending on how you look at it), thus furthering the stereotype that many countries appear to believe: that German comedy is no laughing matter.

Except that, like most stereotypes, it’s completely and utterly bogus.

I give you Exhibit A: Ernst Lubitsch – the man that, according to no less than Jean Renoir, “invented the modern Hollywood.” Lubitsch was a comic genius, an artist, a maverick, a sophisticate, and yes: a German. He was truly a man of infinite jest. And he made films of infinite zest.

The writing process can be a punishing one. Lots of writing can create lots of writhing. To aid this process, and act as a constant source of inspiration, the great Billy Wilder had a saying. While working on a given project, be it a film noir or a screwball comedy, he often asked himself the same question. So imperative was this question to his screenwriting process that he, in fact, had it mounted above his office door. It simply read, “How would Lubitsch have done it?”

Lubitsch was Wilder’s hero. Wilder once said that Lubitsch “could do more with a closed door than most directors could do with an open fly.” For Lubitsch, as Wilder well knew, was a supreme craftsman; and one that also enjoyed great commercial success in his day. He was the golden boy of Hollywood’s Golden Age. And his gilded sheen never dulled. Lubitsch specialised in witty, sophisticated comedies; often poking fun at the upper classes and those in power. As a director, he had an incredibly deft hand. His style was nimble and unexpected; sharp and refined; it was instantly recognisable, and always very funny. As a result of this gentle filmmaking flourish, his films were often marketed as having “the Lubitsch touch”.

The Lubitsch touch is a touch of class. It’s easy to appreciate; impossible to replicate. Instead, one can only bask in its sizzling, sunlit perfection: the subtle touch of an off-screen master. This can be found all over films like “Trouble in Paradise”, “Design for a Living”, “To Be or Not to Be”, “The Shop Around the Corner”, “Heaven Can Wait” and “Ninotchka” – all of which are some of the greatest American films ever made. And I believe Mr. Billy Wilder would thoroughly agree. (Speaking of Wilder, here he is talking about “The Lubitsch Touch” at the AFI Harold Lloyd Master Seminar in 1976. Unsurprisingly, he explains it brilliantly.)

One of Lubitsch’s finest films is “Trouble in Paradise”, a delightfully dazzling Pre-Code rom-com about a gentlemanly thief (Herbert Marshall) and a crafty pickpocket (Miriam Hopkins) that decide to con the famous perfume manufacturer, Madame Colet (Kay Francis). It is an extraordinarily flirtatious film. Its characters candidly flirt with one another for practically the entire running time. And the film candidly flirts with perfection. Like so many of Lubitsch’s films, it is crisp, breezy, superbly sophisticated, and every bit as exquisite as the day it was made.

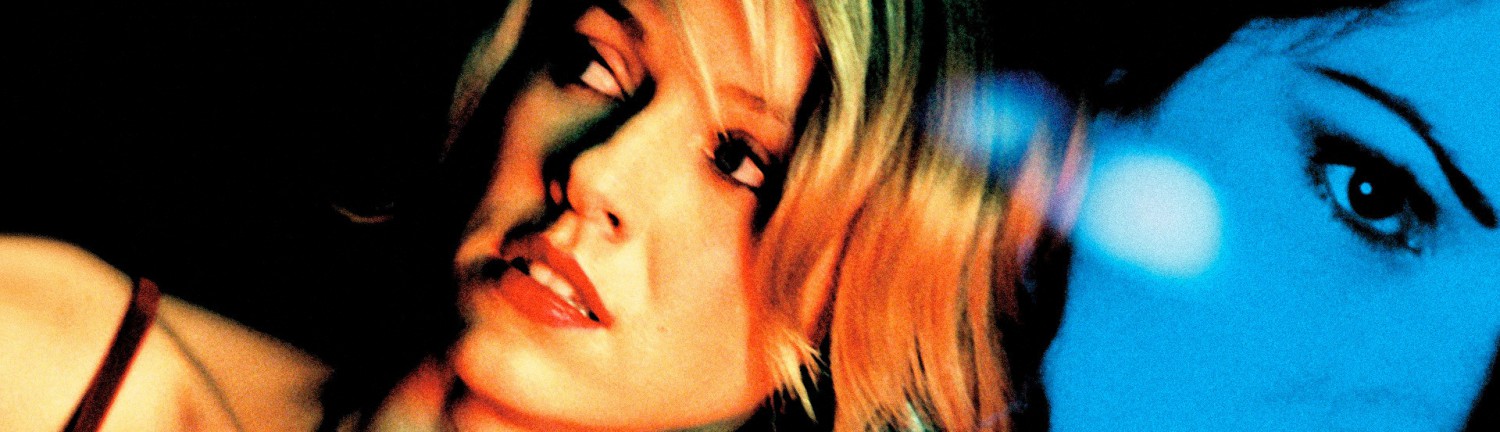

Another Lubitsch masterpiece is “To Be or Not to Be”, a movie about a group of actors in Nazi-occupied Warsaw that get caught up in a plot to track down a German spy. The film stars Jack Benny as the star of a Polish theatre company, alongside Carole Lombard who plays his wife. Lombard was one of the century’s greatest comic actors, and this was sadly her last movie before her tragic untimely death. But Lombard’s death wasn’t the only thing seen as untimely. Released in 1942, the film, too, was greeted with cries of “Too soon!” The New York Times wrote that the film was “callous and macabre”, and it performed terribly at the box office. But today, “To Be or Not to Be” is seen as one of Lubitsch’s best works. And rightly so. It is easily one of the funniest films ever made and true testament to the genius of its director.

What made Lubitsch so special, among many things, was his sense of mischief. His films are littered with adult themes, hinted at through sly visual humour and witty, playful gags. But his films never ventured into smuttiness. If there is such a line that divides smut from genius, Lubitsch never crossed it. But, especially with the advent of the Hays Code, he did sometimes walk it. And for that, I will always love him.

So why does nobody talk about Lubitsch anymore? Is it so hard to acknowledge that a German is responsible for some of Hollywood’s greatest comedies? German comedy is some of the greatest in the world. (Critical darling “Toni Erdmann” is one of the most acclaimed comedies in recent memory. And guess what – German.) Ernst Lubitsch was one of the most famous directors of the 1930s, yet today very few have even heard of him. It’s such a shame. Or, as the Tangerine Tyrant would say, “Sad!”

So this week, in honour of his 125th birthday on Sunday, stick on an Ernst Lubitsch movie. Stick it on and marvel at his German genius, his wicked wit, his supreme sophistication and, of course, that gloriously gifted, tremendously talented touch.