Fellini is one of the greatest artists in all of cinema. The maverick began making films in post-neorealist Italy, producing beautifully realised, often deeply poignant, masterpieces such as “La Strada” and “Nights of Cabiria”. However, the style that has become so synonymous with his work is somewhat weighed down is these early gems by his provincial neorealistic obligations. But then he began to turn his lens to something more personal, something more eccentric—something more Fellini. The true greats of cinema all have their own distinctive look and feel. It’s something intuitive and unmistakable. A single frame of any Fellini film simply could not have been conceived by any other filmmaker. His individualism is undeniable, his craft indisputable. His work is so unique that his name has entered the lexicon of not just cinema, but of art—all art. “Felliniesque” immediately conjures an Italian sophistication; vivacious yet earthly, transcendent yet real. His films involve a captivation for the bizarre and a love of the simplistic, all ornately wrapped in a flamboyant, fantastic approach to life and art. He is a celluloid God: a cinematic Dionysus.

The spoken word is ideal for exploring ideas. Film, however, is made for images. It is a visual art form, and few filmmakers are as visually audacious or as heavily skilled as Fellini. He embraces the medium of cinema in all its wondrous complexities and brings a bubbly, energetic joy. He never fights against the nature of his art, instead allowing images to cascade freely, evoking memories and emotion that are not rigidly bound to preconceived ideas. In “8 ½”, Fellini’s genius is on full display. The film moves in and out of fantasy and reality in such a way that is never obfuscating but wholly cinematic. It leaps from a state of consciousness to memory to one of illusion, outlining one man’s desultory self-psychoanalysis as he searches for inspiration for his next artistic project.

In terms of execution, filmmaking has rarely been better. In creativity, originality, structure, humour, satire, it is stunning by all accounts. It is a visual treat for the eye, a joyous delectation to behold. Cunningly, Fellini has chosen a film director as his subject of introspection—one struggling for vision and clarity as he floats through a milieu of luxury and labour, an experience clearly fabricated from Fellini’s own circumstance. Within this exploration lies the movie’s greatness, for somehow Fellini has managed to craft a work of art from an apparent self-diagnosed inability to create. The act of filmmaking has never been more ironic.

The picture opens in a silent trance, a surreal dream wherein we find Guido (the effortlessly cool Marcello Mastroianni) trapped in his car, suffocating and immobilised. He then escapes through the sunroof into the sky and above a beach, in a perspective that alludes towards Dalí’s “Christ of Saint John of the Cross”. He is suddenly hauled back to Earth by a kite-string attached to his leg. The individual pulling him back to reality is perhaps representative of Guido’s associates, constantly pestering him to arrange the plans for his next feature; interrupting Guido’s escapades from the difficult present to the more accommodating domain of his dreams.

Through his fantasies and memories, he manages to quench his anxieties and doubts towards the value of cinema and the value of his own work. They also serve as a vehicle through which to escape the swarms of persistent idlers and over-zealous job hunters that plague his every move. Through these reveries, we discover a tremendous egotist, a man of supreme idealism and romantic gesture; a man of charisma and casual arrogance who has been tended and spoiled by women ever since his days of youth.

One of the most film’s most famous sequences is an elaborate, feral fabrication wherein Guido envisions himself as the master of a harem occupied by all the women in life—his wife, his mistresses, and many more women that he profusely objectifies. He orders them to perform and attend to his every need, smacking them with a whip and receiving their total adulation whilst in an entire state of elation. The women continually buckle at the knees in this severely indulgent mental concoction that places his ego at the centre of the frame, but also simultaneously subtly undermines it. It is a tremendous piece of cinema.

In other scenarios we see memories altered, and perhaps embellished, by imagination. Film is the perfect medium to explore such abstractions. We see rambunctious schoolmates at the beach leer at the local prostitute, Saraghina. She is depicted as a woman of immense presence—a voluptuous stature with a salacious vibrancy that leaves a lasting impression on a young, adolescent Guido. His punishment by the priests of his Catholic school marks a stark contrast to his encounters with Saraghina. Here he reflects on the guilt of his younger self and the shame imposed upon his mother. A portrait of Dominic Savio (the Italian pupil of “Saint John Bosco” who died at the age of fourteen but whom later became canonised for his remarkable display of “heroic virtue” in everyday life) is hung on the wall of the school. Savio, being the consummate role-model for a pupil at such an institution and a symbol of innocence and integrity, further accentuates Guido’s remorse towards his lack of resolution and determination, unlike that of the young saint.

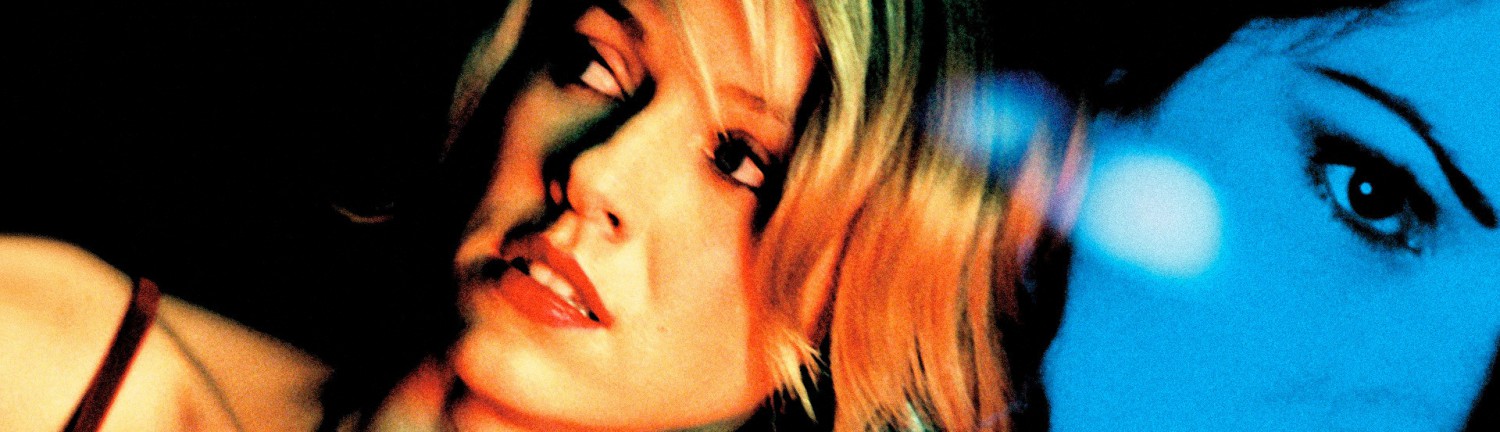

Mastroanni gives Guido the perfect blend of chic, 1960s Italian nonchalance and a haughty air of superiority. He is a man exhausted by those around him and the stifled situation in which he finds himself. His wife (Anouk Aimee) is an elegant intellectual with whom he cares for but cannot connect. His mistress (Sandra Milo) is the opposite—a flamboyant coquette of gaudy taste and colourful mannerisms that fuels his lust. The woman of his dreams is exemplified by Claudia Cardinale—a beautiful, ethereal presence that causes the screen to glisten every time she appears. Her entrance in the film is shown from Guido’s point-of-view: Dressed in the purest white clothing, we see a close-up of Cardinale’s face almost perfectly glide across the frame, for this is how Guido sees her—the fragile, weightless angel that can only be admired from afar. When he finally meets her, the impossible standards that he has projected onto this woman only serve to naturally disappoint. But, in his head, she is his muse; even if this form of her is merely illusory.

“8 ½” is a picture that, when projected onto a screen, doesn’t just reflect, it radiates. This is partly due to Fellini’s attention to movement within the frame and his use of space and focus throughout. Fellini’s fluid camerawork is somewhat atypical when compared with his contemporaries. Antonioni’s consideration of composition and angular set-ups was thorough, but he rarely moved the camera unless there was no other way to make a narrative point. Buñuel also rarely moved the camera unless circumstances dictated that he must—Bergman very much the same. Fellini, on the other hand, embraces the graceful fluidity of the camera. His playfulness is remarkable. He uses the camera the way a child plays with a Christmas toy. But he is never ostentatious. He never moves the camera for the sake of it, attempting to draw attention to the intricate planning that has gone into a particular shot.

In Roger Ebert’s review of “8 ½” in 1999, he recalls visiting the set of “Fellini’s Satyricon” and discovered that Fellini played music on the set of every scene. Like many Italian directors of his generation, he preferred to record sound in post-production. Their main concern during filming was the creation of images—mainly indelible ones. This insight into Fellini’s method makes complete sense with regard to his output. Fellini’s actors dance on screen. They sway, spin, twirl and pirouette within the frame; the music supplying the perfect atmosphere in which to do so. The actors adjust their movements within each scene and bring a subtle rhythm to their performance as demanded by their environment—likewise for the camera operators. They too can mimic the flow of the melody and help produce a seamless confluence between sound and image. Add to this Nino Rota’s wonderfully grandiose score and the result is an incredibly infectious cinematic experience.

Fellini is cinema, and cinema is Fellini—in its most enthusiastic, unbridled form. His films remind us of the tragic nature of existence but also of its joys, its delights and its ecstasies. His films, particularly the latter ones, are never “true” depictions of life, such as it is. They are expressions of life: life in all its complications and contradictions, its ups and downs, its pleasures and sorrows, all rolled into one remarkable vision. In that regard, “8 ½” is one of the purest illustrations of life on screen. It is a rich celebration of life, for life itself is a celebration. In fact, as Guido muses at the end of the film, “Life is a party”.